Max Yoho was burned in a gasoline fire in Colony, Kansas, about two weeks before his thirteenth birthday, in early June, 1947.

His family had moved from Colony to Atchison in the summer of 1945. Two years later Max had just completed seventh grade when his family took a vacation back to Colony, visiting his maternal grandparents, the Christenberrys, and their many Colony friends.

Max and his friend, Billy Don, were playing in the front yard at Billy Don’s farm house on a Sunday morning. The farm was just outside of the Colony city limits. To relieve their boredom they had started a bonfire. The fire didn’t take off the way Billy Don had hoped, so he siphoned a jar of gasoline out of the tractor to bring back and pour onto the fire. Much to his amazement, the flames followed the stream of gasoline back into the jar, scaring the bejesus out of him. His gut reaction was to rid himself of the jar of flaming gasoline, flinging it away...right onto Max, who was squatting near the fire.

It being summer, Max was not wearing a shirt. The flaming gas hit his bare arms and fingers. His jeans caught fire and his belt held the flaming fabric close to his stomach and upper legs. Fortunately, his underwear and crouched position protected his groin and lower legs. Yet much of his body was aflame. Billy Don’s mother saw the horror through a window in the farmhouse and rushed to Max’s aid, rolling him on the ground to put out the fire. She then set about getting him emergency help.

That help involved a ride to Topeka in a fancy Cadillac, a vehicle called for in emergency circumstances by people of Colony who needed chauffeuring services. His mother rode at his side, and they were eventually delivered to the place known today as “Menninger Hill”—and to the building with the tower, still visible at the Topeka skyline, that was then Security Benefit Hospital.

A medical examination determined Max was covered in third degree burns. They gave him medication to curb his pain…and waited. The good news was that his lungs were not burned, attributed to the fact he’d been shirtless and had not breathed in the fire. The bad news was development of a large bubble of blood on his stomach where his belt had held the burning jeans tight to his middle. Doctors feared the fire had burned deeply, and had fatally damaged his digestive system.

Max also received heavy doses of antibiotics in the attempt to protect his wounds from infection. When he did not die within the first week, hospital staff decided to go ahead with aggressive treatment of his burns. Max’s bubble of blood slowly began to recede.

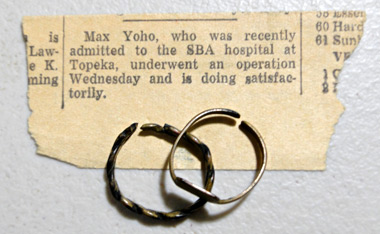

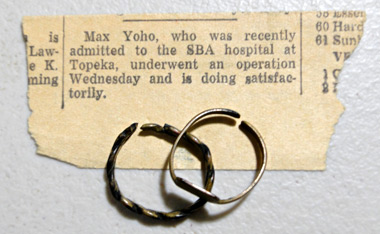

Max's mom kept these rings, cut from his burned fingers and a newspaper clipping. These items were stored together in an envelope, found decades later while storting through family photos.

Treatment included regularly scrubbing away damaged, dying tissue on his torso, arms, hands and upper legs...a terrifically painful process called “debriding.” He was placed in a tub of warm water mixed with saline solution. Max remembers that debriding often made him wish he were dead.

Also painful was bandage removal. Staff came to his room and ripped bandages off of his wounds. They would try to work quickly, but each ripped bandage would be followed by a sheet of flying blood. Again, the pain would cause him to cry out.

Once the bandages were off, Max’s torso was covered with a small tent and the burns were allowed to stay open to fresh air for a couple of hours at a time. Leaving the wounds open was meant as a natural healing aid, but the next step was Max’s least favorite: a doctor would swab silver nitrate crystals, attached at one end of a wooden stick, over his burns. Silver nitrate caused a painful burning sensation and Max could not, again, help but to cry out in pain.

Much later he learned that one young nurse involved in his treatments would slip into the hallway and burst into tears after coping with his cries of pain. Nearby patients also had to learn to endure his screams.

Max’s doctor was a burn specialist, recently returned from treating burn victims among U.S. soldiers during WWII. He took on the job of grafting healthy skin into Max’s wounds using the newest of burn technologies—a process called “pinch-grafting.” Pinch-grafting involved a procedure in which Max’s healthy skin was removed from the fleshiest parts of his upper arms, chest and lower legs—by pinching the skin to raise it from the surface of his body and cutting it off in little, pinched patches—then poking the dozens of patches into his burned tissue, somewhat like planting seedlings, where they could help heal and replace burned tissue. The work was done in two separate procedures. Not all of Max’s pinch-grafts worked but the majority did, and the procedures were considered successful.

Recovery was an arduous regime. Max stayed in Security Benefit Hospital for five-and-a-half months having painful bandage-removal, debriding, and swabbing with silver nitrate. His doctor carefully monitored his progress.

Max’s mom, having arrived at the hospital with him, lived at his side for the entire duration of his stay. She slept at his bedside every night and represented family in all treatment decisions and procedures. Max’s dad and older sister came from Atchison to visit him on weekends.

Max’s thirteenth birthday in mid-June was memorable. His dad arrived with the promise of giving his son a family member’s Winchester 70A .22 rifle as a birthday gift when he came home from the hospital. Max was truly excited about that promise.

There was neither television nor computer gaming in 1947, but Max remembered listening to the radio to help pass the time. Also, family and friends provided comic books as in-bed entertainment. His collection grew to be a large stack, including Superman, Archie and Friends, and Donald Duck among many other 1940s comic heroes.

In mid-treatment Max asked his Dad to bring him a piece of gravel. As he held the large chunk in his hand, tracing its contours with his fingertip, he felt it was an important link to the outside world—an Amulet of Hope. He longed to go outdoors again, and found comfort in holding the stone.

He also enjoyed alcohol backrubs given him by one particular nurse’s aide. It was extremely hard for him to turn onto his side, but once he managed the turn, cool backrubs relaxed his muscles and comforted the bed sores that continually developed on his back from spending months lying burned-side-up in bed.

As Max got better, staff would place him in a wheelchair and push him down the hall to the hospital solarium—a sunny, inviting space that was a welcome change of scenery. In the solarium he enjoyed drinking bottles of Grapette soda. There, he was entertained by talking to one particular older lady who was another long-term resident at the hospital. (Security Benefit was known to take care of their insured clients “from the cradle to the grave.”) This woman had claw-like hands from debilitating arthritis. She was always nice to him, and once gave him a golden-colored glass cup with a ribbon, tied into a bow on its handle. The cup was too small to use, but he appreciated her kind gesture of giving him a gift.

Max was released from the hospital in December, 1947, and arrived home just in time to celebrate Christmas. However, his healing was not complete just because he had been sent home. He had been confined to bed for his entire hospital stay. His legs would not straighten nor hold his weight. He depended on a wheelchair, and it was up to him and his family to see that Max worked at stretching his leg muscles. No physical therapist was involved but, eventually, his legs loosened and straightened enough to begin bearing his weight. He began to practice walking again, relying heavily on crutches. His at-home therapy took an additional six months.

One black and white photo shows Max sitting in his wheelchair at an open side-door of his Atchison home. He sits inside, but is enjoying fresh air and sunshine. He has a flashlight strapped underneath each armrest of his wheelchair. When I first saw the photo I asked, “Did you use these lights to find your way to the bathroom in the dark?”

“No.” he said, “Those were just my headlights. I used them regularly. I also had a doorbell rigged onto the chair. I would ring it to warn my family when I was headed their way.” Oh, the friskiness of a thirteen-year-old!

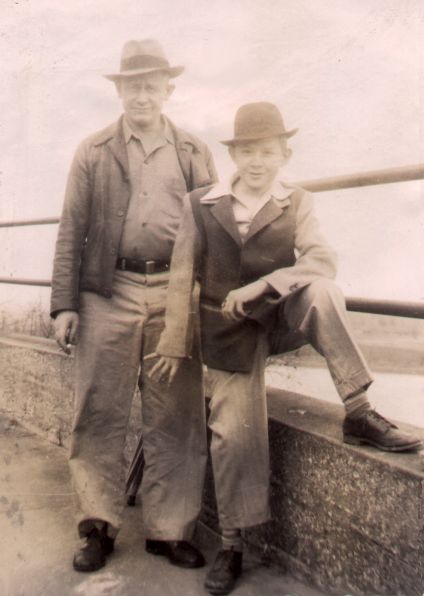

Several photos show Max standing outdoors on the day of his first trip outside the house. It is early spring. Max wears a jacket and a dapper hat. In one photo he stands tentatively. He is supported, physically and emotionally, by his mother. He is obviously happy.

In another photo taken on that momentous day, Max sits on a log on the western bank of the Missouri River, one block east and down a steep hill from his home on Atchison’s North 2nd Street. Max loved the river above all other Atchison landmarks—and loves it still. Again, his smile at being outdoors and, this time, sitting close to the edge of his beloved river, is genuine!

My favorite photo of Max was taken that same April day. Max is balanced on a pair of crutches and stands on the steep, sloping alleyway behind his house. His legs are still bent from his burns. He has his thumbs in his ears and is wiggling his fingers at the person with the camera, while he sticks out his tongue. This is a boy with a pesky attitude, despite everything he has been through. In that photo I see the Max I know and love, the person who has overcome incredible adversity—the person who loves life and refuses to capitulate!

His accident caused him to miss one full year of school. He started eighth grade in fall semester, 1948, as his former classmates began their ninth grade year.

Max says surviving his burns has made him patient and practical. His experiences showed him what is important in life, and made him love and appreciate more deeply his family and friends. The ordeal also aided his judgment in deciding what situations in life really aren’t worth the trouble of stewing over.

In the decades since his accident, clothing usually covers most of Max’s burn scars and the many “dots,” lacking skin pigment, where pinch-grafts where made from his healthy skin. He copes with these scars quietly, as a matter of fact—but his scarred flesh still bothers him physically, tending to dry easily and tighten. Today’s doctors and nurses stare at these markings in amazement. They ask; but most have never heard of “pinch-grafting”—as newer grafting techniques prevail.

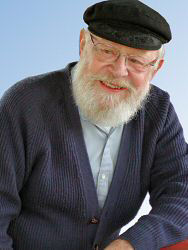

Max finished his secondary education in Topeka, after his family moved there in 1949. He had vocational training and a few college classes. He married, raised a family of three sons, spent eight years as a widower, took up writing after having retired from a thirty-eight year career as a machinist. He has since written five novels and one published collection of poems, essays and short stories. He is grandfather of five, great grandfather of six, and will celebrate his 80th birthday next June.

I find it particularly interesting that Max’s writing often focuses on coming-of-age adventures. Boys face becoming adults and try to determine just what the transition will mean to them. They have fun, face problems, get into trouble, then persevere. These characters of Max’s fiction each live, with humor and adventure, a year which Max missed entirely in his own life. Few people reading Max’s work know his personal story, but learning of the extent of his tenacity makes reading his work even more amazing!

above: Max sits at his home's side door. His wheelchair is equiped with headlights & a doorbell "warning" option.

above: Nellie Yoho continues to support her son—his first trip outdoors, ten months after his accident.

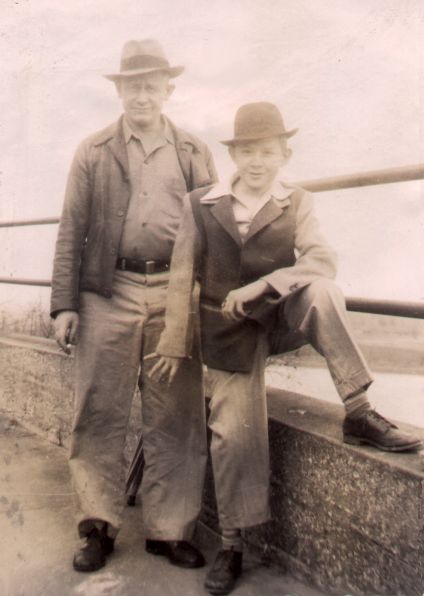

above: Lloyd Yoho with his son—high above the Missouri River.

above: Max sits on a log at the west edge of the Missouri River at Atchison.

above: Max balances on crutches in the alley behind the Yoho home in Atchison.

|