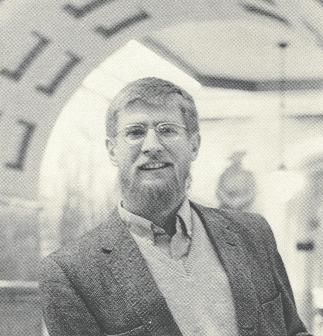

THOMAS FOX AVERILL

For the month of June, 2000, I introduced another old

friend, one of Kansas's most distinguished authors (and my office mate

for thirteen years), Thomas Fox Averill. I returned to consider

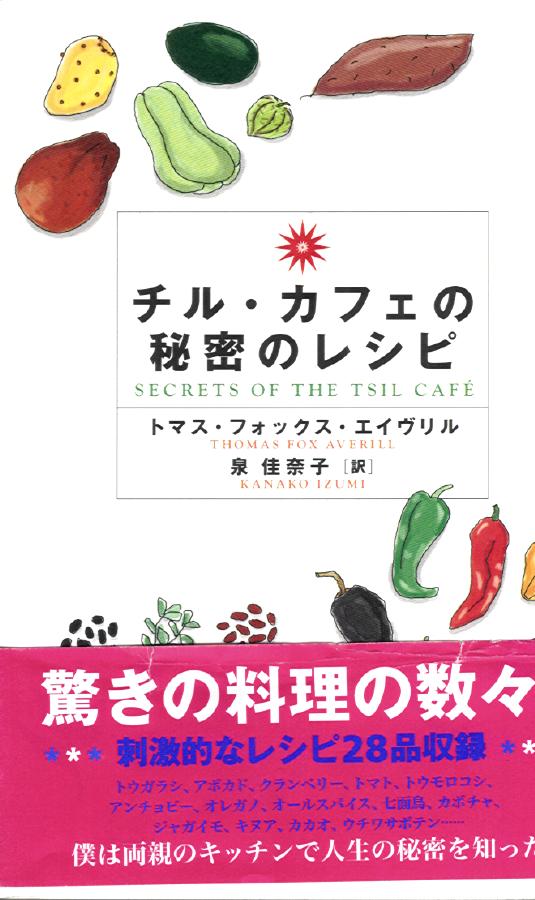

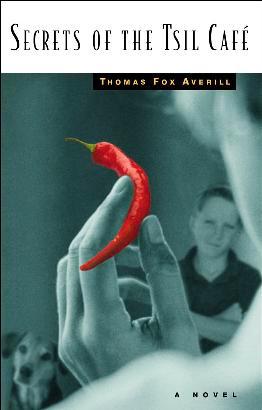

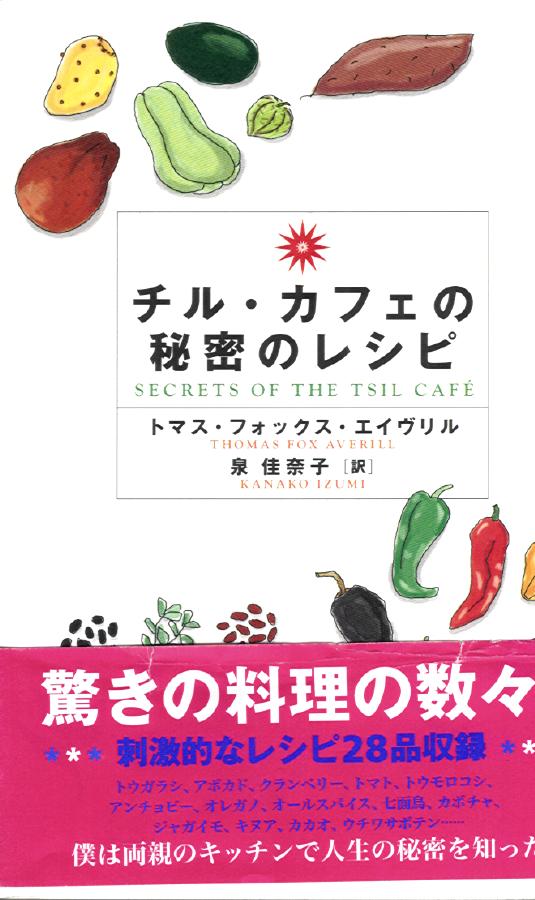

him again in August of 2001, when he published the novel, Secrets

of the Tsil Cafe. From March-June, 2003, I again

featured Tom, after the Japanese translation of that novel was published,

demonstrating that a Kansas writer can indeed reach out as far as Japan.

_____

_____ _____

_____

THOMAS FOX AVERILL

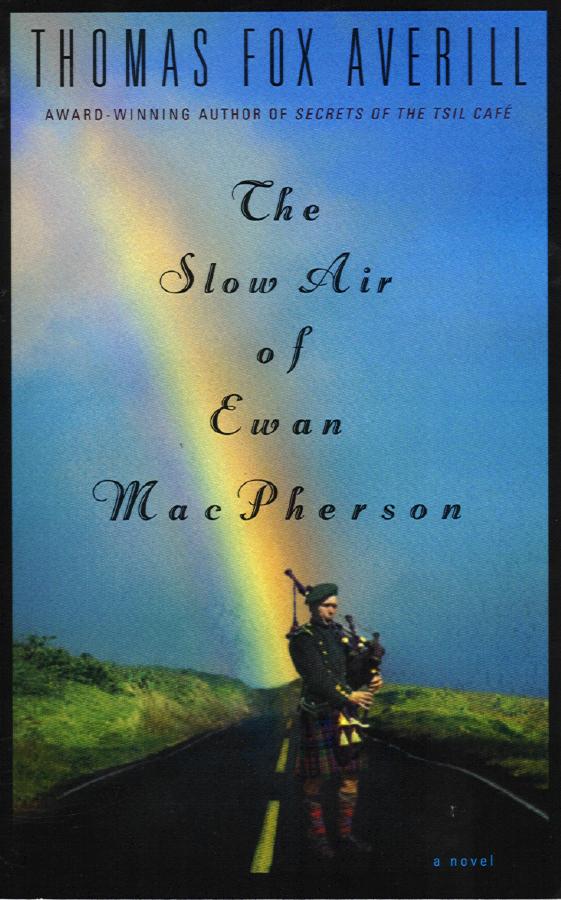

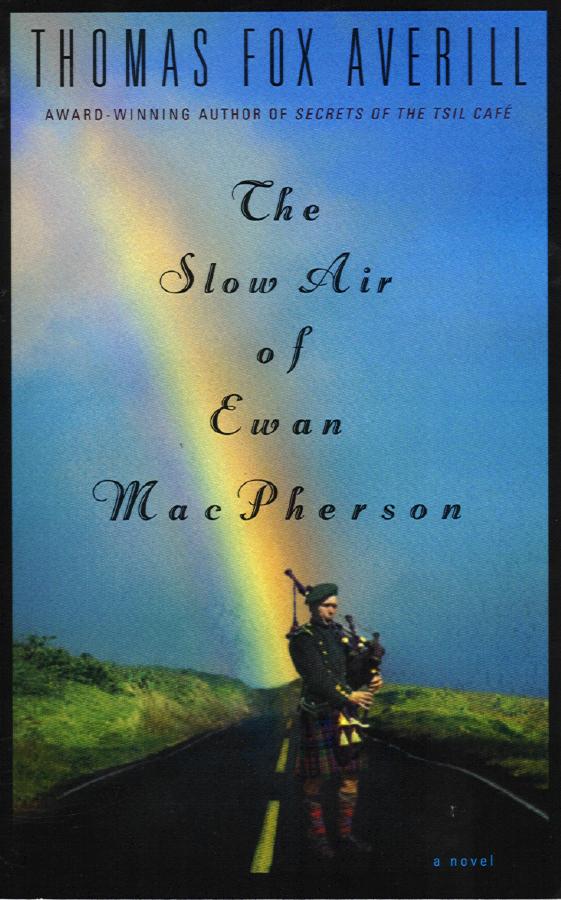

Now Tom has published a new novel, The Slow Air

of Ewan MacPherson, "a full-bodied novel of love, family, friendship,

self-discovery--and single malt Scotch."

___________

For more extended comment and example of some

of his work, you can hit this link to my longer piece on Tom

Averill,

or switch to his own web site: <http://www.washburn.edu/cas/english/taverill>.

Bob Woodley was my office mate at Washburn University from 1963 until

his death in 1976. Tom Averill was my office mate, in the same office,

from 1980 until I retired in 1994, so for about the same number of years.

And, in one important respect, they did the same thing--taught creative

writing--were the creative writing program at Washburn. But

the program has burgeoned under Tom, who is a charismatic teacher, until,

these last ten years, it has required an additional teacher.

And, beyond this, Tom's teaching specialty is Kansas Literature.

In fact, if anyone's name suggests "Kansas Literature" to almost everyone

who hears it in the state of Kansas it is Tom Averill's. I think

it is fair to say that Tom does know more about Kansas writers, living

and dead, than anyone else, living or dead, ever has. And he has

absolutely educated himself in the field, by getting out and about and

working with living Kansas writers--like Robert Day, Steve Hind, Harley

Elliott, and Bruce Cutler--and with others who've made a specialty of Kansas

History, including earlier Kansas writers--like C. Robert Haywood, Robert

Richmond, and Gene DeGruson. Then he taught courses, across the state,

focusing on local writers in their local libraries (in connection with

which he did a map of Kansas Literature), then in the classroom at

Washburn, and then (the definitive version, I would say) on television,

when he did the television series on Channel 11 that may be the best TV

course they have done. That course has been offered many times, and

has always drawn a strong enrollment. I have most of the half-hour

segments on tape, but would still tend to watch the rest of the show whenever

I happened to turn it on, since I often knew the people he was talking

about or interviewing--and since he is a particularly good interviewer.

They are interesting and informative programs, which I recommend to anyone

interested in Kansas Literature.

So I knew Tom well as an office mate and teacher. But then I have

also worked with him, over the years, on the Woodley Press. We had

started the press just before Tom came to Washburn, but then published

his first collection of short stories, Passes at the Moon,

in 1985, as our seventh book, and re-printed it in 1990. But it has

long since been out of print--so, much as I would like to, I can't promote

the sale of that book. But Tom also had three stories in Kansas

Stories, 1989, edited by James Girard (which is still in print);

he was on the board for years; he edited Harley Elliott's The Monkey

of Mulberry Pass for the press in 1991; and then he was the president

of the Woodley Foundation for 1997-98--so has strong connections with the

press. At the same time, Tom was instrumental in developing the Center

for Kansas Studies at Washburn, and has edited five books under that aegis

(The Kansas Poems, Kenneth Wiggins Porter; Dust and

Short Works, Marcet and Emanuel Haldeman-Julius; As Grass,

EdytheSquier Draper; In a Place With No Map, Steven Hind;

and A West Wind Rises, Bruce Cutler--all still in print)

the last two in conjunction with the Woodley Press. Tom has done

a

lot of editing, notably What Kansas Means to Me (University

of Kansas Press, 1991), seventeen essays by well-known Kansans (including

William Allen White, Karl Menninger, and Milton S. Eisenhower, as well

as William Stafford and Denise Low). That book, too, is still in

print, and there are many things in it I might use as a sales enticement,

but they are by other people. Tom's second collection of short stories,

Seeing

Mona Naked (Watermark Press: Wichita, 1989) is still in print as

well, and I am tempted to offer a story from that, or one of the many stories

that he has published in periodicals since then (say one that won one of

the O. Henry awards) for Tom certainly deserves his reputation as one of

the finest writers of short fiction in the state.

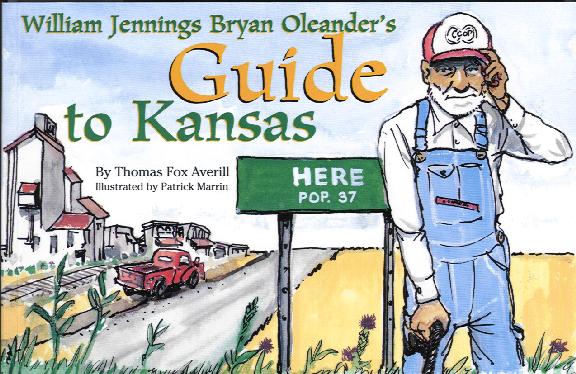

But I have decided to feature the work that has already been Tom's most

successful, William Jennings Bryan Oleander's Guide to Kansas (Wichita

Eagle and Beacon Publishing Co., 1996), for it brings Tom's connection

with Kansas most strongly into focus, I believe. Tom developed the

character of William Jennings Bryan Oleander primarily as a radio persona

on KANU, Public Radio, University of Kansas in the early '90s, first once

a month, then twice a month, then every week during the 1995-6 legislative

sessions (after Oleander was elected to the legislature from Here, Kansas).

Oleander's comments were also printed in the Topeka Metro News,

were put on tape, and Tom came to make more and more personal appearances

before groups of all kinds in the state as William Jennings Bryan Oleander,

which he does very well. So now there is the book, there is the tape,

and, if you need a program you couldn't do better than to have Tom come

to tell you about some aspect of Kansas from the point of view of this

character he invented, and then perhaps talk about the character as a fictional

creation afterward. He wrote a prizewinning play on the character

which was produced at KU three years ago. And I don't know of any

better way to get you into Tom's take on Kansas than the opening essay

from that book.

Here, Kansans Live in Small Towns

Folks, I'm William Jennings

Bryan Oleander. The William Jennings Bryan is for the great "Boy

Orator of the Platte," the great "Popocrat (half Populist/half Democrat),

the People's Hope at the turn of the century in the presidential election

of 1896, when it looked for a hopeful moment that the common people might

grab control from the moneyed, self-interested corporations. I'm

proud of my name.

So what if William Jennings

Bryan lost in 1896? And again in 1900? And in 1980? So

what if Bryan went from great political orator, to Chautauqua lecturer,

to honorary prosecutor of that evolution-teaching John T. Scopes in the

great Scopes Monkey Trial? So what that Bryan was mercilessly upstaged

by Clarence Darrow? So what, in short, if Bryan was best known for

his repeated failure to become president and his failure to return a Creator/God

to the schools before his death in 1925, five days after the Monkey trial?

I'm still named after a famous man: just ask my daddy, Abraham Lincoln

Oleander.

Not a one of us Oleanders

knows where the Oleander comes from. We know the oleander is a plant;

we know it grows well in Kansas; we know it's poisonous in all its parts:

berry, leaf, stem, branch and root. Has that shaped me and my kin?

Well, we speak our minds; we let folks chew into us and spit us back out;

we grow where we're set without fear of enemies; we're not nourishing but

we have our beauty, our elegance, our place in the world, and in Kansas.

And since the early days

of the state, that place has been Here, Kansas. Now don't go hustling

to find your latest Kansas Department of Transportation map of the Sunflower

State: You won't find Here, Kansas.

Who would want to get here?

A failed bank and a closed-down post office share the same old limestone

building. To get a money order, you drive over to Near Here (don't

look for it on the map, either) and see Harvey O'Connell at the Near Here

Tavern and Mini-skirt Museum (don't get too excited--it's just one mini-skirt

that young Harv scavenged from that bus wreck in 1972).

Everything else we need

is in Here. Young Claude Hopkins down at the Mini-Mart will cash

a Social Security check. Co-op has a screen door and a flyswatter

in the summer, a woodstove and a checkerboard in the winter. Elmer

Peterson's Drive-Thru Pharmacy and Car Wash keeps us clean and medicated.

You see, most of us in Here are what you'd call over the hill, only there

aren't any hills out here to be over. Why, it's so flat you

can stand on tiptoe and see grain elevators in five surrounding counties.

Our tallest citizen is Barney

Barnhill. We call him the "Weatherman" because he's so tall he sees

storms rolling in five or ten minutes before the rest of us. Barney

runs Here's great tourist attraction, the Demolition Derby Museum, open

from 3:45 to 5:00 the first and fourth Friday of most months, and 8:00

until closing every other Saturday except in months beginning with "J"

and "A." Come see us. Barney will talk your ear off about the

history of those Kansas Demolition Derby Curcuit cars.

Folks, for the last several

years, since I turned ninety, I've been the honorary Mayor of Here.

We used to elect someone, until election expenses became our entire budget.

Plus the drawback of working with Hattie and Tommy Burns. They're

the cultural sector of Here, Kansas. She's a hairdresser. He

repaired speedboats until Here Lake dried up. Together they run the

Here College of Beauty and Fiberglass Maintenance. They're Here boosters.

Once a year they put an ad for Here and the College in the Wichita paper,

then sit back waiting for a rush of discontented city folks. When

nobody shows up, they get mad and try to charge the ad to the city.

It's my job to say, "Nope, Here won't pay."

You see, Here, Kansas, was

founded when a bunch of our ancestors strayed from the Santa Fe Trail.

They didn't know where they were going. They were as whiney as a

bunch of kids. "Are we here yet?" they kept asking the wagonmaster.

Finally, he sneaked away one night. They weren't smart enough to

know they'd been abandoned. They thought they'd arrived. They

called the place Here, and we've been here ever since.

In the early days, we boosted

the town, took ads in the Eastern papers, brought in reporters from Topeka,

lied ourselves red-faced for nothing. Every one of us traces our

heritage to that original wagon train. If you can't find us on the

map, that's okay; we've been lost most of our history. And being

lost means we haven't often been found. Think about that advantage:

We haven't found crime, nor welfare, nor teenage pregnancy (try to find

a teenager in Here!), nor local car dealer commercials, nor Kiwanis clubs,

nor salad bars, nor a sign on the highway that reads "Welcome to Here,

Kansas, Population 38."

But being lost also means

we've remained true Kansans: unadorned, unalloyed Kansans. Here is

the unvarnished truth about Kansas, without the propaganda of state government,

economic development, or the Kansas Department of Commerce, Travel and

Tourism.

Let me give you an example:

You know how state officials are always talking about something they call

the Brain Drain? Of course the politicians want you to think Kansas

has Brain Drain because our kids leave the state after a stint in one of

our Margin of Average colleges. But in Here, we see the Brain Drain

from the local view. For lots of us, Brain Drain is a personal problem.

And we don't get it from leaving the state. Hell, we get it from

staying. And Here is the only Kansas community doing something about

it.

You see, back toward the

end of W.W. Two, J.W. Small needed help. J.W. and his wife, Minnie

Small, were set to adopt a war baby, clear from France. Folks in

Here had never seen an honest-to-God French person--Frogs they called them

back then--let alone a tadpole. The whole town was ready to welcome

that baby when J.W. panicked. Held a town meeting. Invited

a professor from a junior college two counties over. J.W. told us

what was wrong. The professor laughed, told J.W. he didn't have to

learn French, the baby'd start right out talking English.

"How can it be?" asked J.W.

"The baby's French. Says so on the papers." J.W. only wrote

a thank-you to that egghead professor after the baby started right out

speaking American. First words: "No" and "wee, wee" (he was a little

pisser).

So, in 1944, J.W. founded

the first group in Kansas to recognize Brain Drain. He called it

DENSA, a support group for thick skulls, slow thinkers, numbskulls; for

the dull-witted, dizzy, and dense. To join, you just confess you've

got a drained brain, then try to remember when the meetings are.

Our mascot is the scarecrow from The Wizard of Oz: his head may be stuffed

with straw, but at least he has something up there.

Now, DENSA likes to keep

busy. I'll give you a for instance. Pierre Small, who has grown

up to be our lifetime president, became very worried when one of our citizens,

Fred Pete, died recently, leaving behind a blind dog, whose name is Revor--that's

Rover spelled backwards.

Pierre went around with

a sign-up sheet, asking everyone in Here to take a turn as a seeing-eye

person for that blind dog. He wanted folks to make sure the dog didn't

get run over crossing the street. Folks willing to spot a cat or

two. Or a fresh load of garbage. "A dog," Pierre told me, "oughta

be able to be a dog, even if it is blind."

"That's right," I said,

and signed up for an hour.

"Make sure you do dog things,"

he said.

"Don't worry," I said, "I

know where every fire hydrant in Here is, and if we run out, I'll take

him to Near Here."

But Pierre didn't stop there.

Why, one afternoon Pierre was almost run over by a lost truck. His

eyes were squeezed shut. "Watch where you're going!" I shouted at

him.

"Is that you, William?"

he asked.

"Open your eyes."

"I can't," he said.

"This is part of my sensitivity training. If I'm going to be a seeing-eye

person for Revor, I've got to feel how hard it is to be blind."

"Where's that darn dog now?"

I asked.

"I don't know," Pierre admitted.

"I lost him."

"And you're looking for

him with your eyes closed?"

"See what I mean, William,"

said Pierre, finally opening his eyes. "Do you see how hard

it is to be blind?"

Lord, folks, when I saw

Pierre next, he'd finally found the dog. He was practically dragging

Revor down the street.

"Frustrated?" I asked him.

"Darn and mon dieu,: he

said. "I swear this dog is so blind it doesn't know where it wants

to go."

Folks, you could say the

same about DENSA, and maybe about Here. But that's only if you're

an outsider. We insiders aren't afraid to be who we are: Kansans;

Here, Kansans; lifetime DENSA members.

* * *

* *

Tom has been very much in demand as William Jennings Bryan Oleander,

is also an excellent reader of his own stories if you are looking for a

literary program, and has a number of books for sale in addition to:

William Jennings Bryan Oleander's Guide to Kansas, Wichita

Eagle and Beacon Publishing Co., 1996

Seeing Mona Naked, Watermark Press, 1989

What Kansas Means to Me, essays by well-known 20th century

Kansans, University of Kansas Press, 1991

Secrets of the Tsil Cafe, Bluehen Books, 2001

Most of these may be purchased directly from the author, at zzaver@washburn.edu

(or see his own web site for more information, at):

<http://www.washburn.edu/cas/english/taverill>.

_____

_____