|

Veterans Day Ceremony, Washburn University, Nov. 11, 2004 —by Roy Bird, Guest Speaker |

|||

In the spring of 1865 a college that became Washburn University was established in Topeka, the Kansas capital. A few young Topekans had worked diligently for more than a decade to secure the benefits of a college to attract population, educate citizens, promote their community's stability, and for economic development. A transfer of property in 1861 had sealed the deal between the Congre-gationalist Church's General Association in Kansas and the college trustees. “Col. Ritchie having gone into the army sent me a power of attorney to execute with his wife a deed to the land,” according to trustee Harvey Rice. “Mrs. Ritchie and myself executed the first deed to the college site where Washburn now stands. On account of the war nothing more was done until 1865." President Abraham Lincoln's name, in the minds of the college founders, was synonymous with the Union and freedom and, therefore, “appropriate for a College whose establishment was sought by those who would perpetrate civil and religious liberty.” On a trip east, as agent of the trustees, Samuel D. Bowker, who had been in a Union Kansas regiment, called on the President, who approved the proposed college. Bowker wrote “that the success of this institution was a matter of deep concern to President Lincoln, and that, during the week of his re-inauguration, he expressed to me His cordial approval of its design and gave assurance of his prospective aid in its Behalf.” Lincoln's tragic death just two months after the launch of the Kansas college—until that time called sometimes Monumental College and sometimes the Topeka Institute—promoted a circular entitled “Lincoln Monumental College” calling the institution “A monument to the Triumph of Freedom over Slavery” and indicating that it was “Dedicated to the Memory of Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, From March 4th, 1861, to April 15th, 1865.” Lincoln's assassination so enshrined his name in the hearts of Kansans that no one argued over renaming the Topeka Institute. Although the President's death prevented the aid Lincoln proposed to Bowker, the memorial idea was used prominently in future campaigns to raid funds for the college, now called Lincoln College. The Civil War and Lincoln's death greatly influenced the early history of the Congregational college. The coming of the war stop-ped promising progress. The donation of a farm southwest of Topeka by John Ritchie—veteran of the Fifth Kansas Volunteer regiment and colonel of the Second Kansas Indian Home Guard Regiment—revitalized the project, and he signed the deed on a drumhead on the field of war in March, 1865. At the close of the war, Lincoln College invited all Union veterans residingin Kansas to attend tuition free, but only eight young men responded. Col. Ritchie's original deed had been ineffective because the founders had not yet incorporated. Thus no legal governing body existed to accept the gift. The new deed, signed in the field before Ritchie was mustered out, included 160 acres on which we now stand and $2,400 in cash. Meanwhile, the trustees purchased lots on the northeast corner of Tenth Avenue and Jackson Street for $400, also provided by John Ritchie. Here on a long-gone ridge overlooking the site where the capitol building would rise, they planned to start the college. The Tenth and Jackson site was selected for a building. Harvey Rice constructed that building after contractors failed to bid because, as one of them told Rice, “it took money to put up buildings.” Rice proposed to build it at a cost of $7,000. He used Union soldiers stationed in Topeka to excavate the foundation. He used stone from a quarry on some of Ritchie's property, and his own “three yoke ox team and two two-horse teams” to haul lumber from Atchison and Leavenworth. In preparation for the grand opening of the college, the trustees appointed faculty who would continue to influence the institution. Some of them were Union veterans who had been teachers and who now returned to their civilian occupations. |

The contributions of Civil War veterans was acknowledged when the Washburn campus was visited for the only time by a U.S. president while in office. In September, 1911, William Howard Taft dedicated the flagpole north of the old Thomas Gymnasium. This flagstaff and the mosaic tile base were given to Washburn by the Topeka members of the Grand Army of the Republic, surviving veterans of the Civil War's Union army. The G.A.R. had invited President Taft to dedicate the new Memorial Building (which now houses offices of the Kansas Secretary of State and the Kansas Attorney General) on the site of the Lincoln College building at Tenth and Jackson. Taft was invited also to dedicate the flagpole at Washburn because of its strong ties to the Union during the Civil War and because it, too, was a G.A.R. donation.

Veterans of the Second World War have been called by Tom Brokaw “the Greatest Generation.” On this day when we honor all veterans, I would add that so, too, were the veterans of the American Civil War. They helped make Kansas a free state; they helped save the Union; they helped to shape Kansas and Topeka and make them what they are today. And they created this great institution of higher education—right down to the very ground—of which we are all so proud today. |

||

Your Local Grocery Store Revisited |

Buildings can be of small towns. But perhaps a personal, retrospective journey back to my favorite Tipton business might provide some insight. The business, known regionally as Schmiedeler's Store, was that of my grandparents and parents. The period for my time traveling is the 1950s and 1960s so my musings are, in effect, childhood memories. The period is significant, however, in that it represents a stable chronological bridge between the 1930s and 1970s and is therefore revelatory of localized business relationships of the earlier period and of the changes in them that transpired as rural Kansas society left one era and gradually entered a very different one.

Osborne branch that originated in Salina. The depot agent transferred the coal to his pickup and delivered it with good cheer to the lean-to coal shed made of tile blocks and abutting the back of the store. It was the job of everyone who worked in the store, but especially the children, to fill the scuttle and to keep the fire going. As a source of warmth, the pot-bellied stove performed like any other stationary glowing orb; it delivered heat energy only so far. On the coldest days the front of the store was more frosty than toasty, and ice formed frequently on the inside of the great front window panels. But, of course, this heating imbalance created some of the ambience of the store as shoppers would first mingle about the stove, warming hands and feet as they leaned forward on the black veneer wooden chairs that probably once served duty in the local movie theater. My brother, Jack, recalled that in his pre-school years he often took naps "When the freight arrived at the store, we were expected to be there." on top of the men's overalls near the warmth of the stove. The heyday of burning coal for heat in local businesses and residences had long passed by the mid 1950s and so the pot-bellied stove in our store went the way of the operator-assisted telephone call sometime near the end of the decade. Although the new, forced-air, gas-burning unit was suspended from the ceiling in the vicinity of the old stove, the space surrounding the place of the old stove never again felt as warm. |

The Protestant work ethic was alive and well in this Catholic community and my siblings and I were introduced to store chores at a very early age. Stocking shelves or "packing out freight" was the one task that you could count on every week. This activity is still rather l “The magic of Christmas

permeated the store as well.” repository for fifty-pound, gunny sacks of peanuts, Brazil nuts, walnuts, pecans and hazel nuts. Although acceptable Christmas fare, these nuts could not compete with the specialty candies that came to the store then. They includes a wide variety of bulk hard candies sold from tin, drum-shaped containers and an equally broad assortment of soft candies, the bulk of which were chocolates that arrived in cardboard boxes. Peanut clusters, peanut brittle, cream mounds, stars, turtles (a type of nutty, caramel chocolate), and orange slices were among the confectionaries I recall, but there were many others. They were sold in bulk or packaged in plastic bags. There was no shortage of labor for bagging chocolates as there was for “sacking” ten-pound bags of potatoes at other times of the year. Even as youngsters we joked about having to “try the chocolate to be sure it wasn't spoiled” in shipment. Above the aisle and spanning the length and breadth of the store were wires festooned with garlands and with green and red wide ribbons. Putting up the decorations was a lot of work, but the anticipation of what was to come made it fun. Taking them down was the low point of the winter. |

Kansas Studies Courses— |

Spring 2004 offerings include:

|

|

Professional Archaeologists of Kansas Prepare for “Kansas Archaeology Month” in April —Margaret Wood, Sociology and Anthropology |

|

t their general membership meeting in t their general membership meeting in October the Professional Archaeologists of Kansas (PAK) began planning a month long, statewide celebration of Kansas' historic and prehistoric heritage. The objective of Kansas Archaeology Month is to raise awareness of Kansas' important archaeological heritage and to promote conservation of our irreplaceable sites. During the month of April 2005 PAK members will be busy presenting lectures and films, organizing artifact identification days, and presenting special museum exhibits related to this years theme, “Faces of The Past.” Kansas Archaeology Month has a long history in the State and in the past was primarily funded by the Kansas State Historical Society (KSHS). Due to State budget cutbacks, however KSHS was no longer able to support this important event. In 2002 the Professional Archaeologists of Kansas stepped up to the challenge and have been hosting Archaeology Month events ever since. Last year Governor Kath-leen Sebelius signed a Proclamation officially declaring April “Kansas Archaeology Month.” One of the important missions of PAK is to facilitate outreach and education. As part of Archaeology Month last year PAK members prepared lesson plans for grades six through eight, which meet Kansas Board of Education standards and have provided annotated bibliographies for teachers and students. These are available on PAK's web site at: www.ksarchaeo.info/ |

Each year PAK also distributes hundreds of posters to schools and other institutions free of charge. Copies of posters from past years are also available on PAK's website.

|

Kansas Geography Field Trip 2004 —Tom Schmiedeler, Geography |

|

| After the river road site, the group proceeded to a geoarchaeological site about 20 miles west of Topeka in the vicinity of Paxico. The precise location was at a cut bank and point bar on Mill Creek, a major tributary of the Kansas River. Rolfe Mandel from the Kansas Geological Survey discussed artifacts found at the location, referred to as the “Claussen site” by researchers. Some of the artifacts date from about 10,000 years before present. Rolfe also explained the geomorphic history of the valley in the Holocene Period of the last 10,000 years. The focus of the field trip shifted to the historical geography of Lawrence on the third stop of the tour. Tom Schmiedeler explained how the early physical geography of the city, particularly an early ravine running through the city in what is now Watson Park in downtown Lawrence, influenced the development of the Old West Lawrence neighborhood. He also spoke of the |

separateness of North Lawrence in its early history. After this meeting at the old Union Pacific depot in North Lawrence, the group crossed the river and had lunch at a number of venues in downtown Lawrence.

|

| Fellows News, from September Center for Kansas Studies Minutes | |||

Bob Lawson, English, noted his book, The Collected Sonnets of Robert N. Lawson, has just been published by Woodley Press. A book signing was held on in the Union bookstore on September 9. Bill Roach, Business Administration, reported Bob Beatty and Mark Peterson, Political Science, presented a paper with a Brown vs. Board theme in Canterbury, England in September. Center funds will help complete their project, which involves a documentary film, accompanying book on Kansas governors, and analysis on the role and function of the Chief Executive in Kansas politics and policymaking. The final phase of the project involves filming of the final interviews and details. |

Carol Yoho, Art, encouraged support of the Kansas Authors Club Centennial Convention to be held at the Topeka Capitol Plaza, October 22-24. Events include a variety of workshops (including one on sonnets by Center fellow Robert Lawson) and featured speakers. Convention details are available online (http://skyways.lib.ks.us/orgs/kac/). Carol continues her website work for the Center throughout the 2004-05 academic year. She encourages Tom Averill, Writer in Residence, English, announced that the Food Colloquium, in the developing stages last spring, is off and running. The Center is supporting event speakers. Also, the next annual Speaking of Kansas Series will include two poets and a fiction writer. Tom announced a new collection of Kansas stories to be published in February by the University of Nebraska Press

|

||

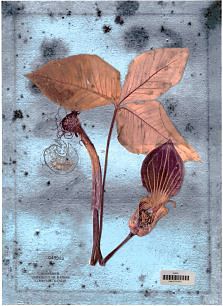

Noted K.U. Anthropoligist to be Kansas Day Speaker Don Stull, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Kansas, will present the Kansas Day lecture sponsored by the Center for Kansas Studies. The lecture is tentatively scheduled for Friday, January 28 at 4:00 P.M. For more than thirty years Don has conducted basic and applied research throughout the United States. Since 1987 his research interests have focused on the impact of the meat-and poultry-processing industries on workers and their host communities as they struggle to meet the challenges presented by rapid growth, rapid industrialization and increasing ethnic diversity. Don directed a team of six social scientists in a Ford Foundation study of changing ethnic relations in Garden City, Kansas. Since then he has conducted research in Lexington, Nebraska and Guymon, Oklahoma, and he has served as a consultant to a number of communities on the plains and prairies of the United State and Canada. He has authored or co-authored more than fifty scholarly articles and book chapters, and three books including the most recent Slaughter House Blues: the Meat and Poultry Industry of North America (with Michael Broadway; Wordsworth, 2004). Art Faculty Show : Mulvane Art Museum, Oct. 16 through Dec. 5 This biennual showcases the work of Washburn art faculty. Gallery hours: Mon., closed; Tues.-Wed., 10 AM to 7 PM; Th-Fri.,10 AM to 4 PM; Sat.-Sun., 1-4 PM. CKS Fellows involved include Mary Dorsey Wanless, Marguerite Perret and Glenda Taylor. HORTUS BOTANICA : Focus on the artwork of Marguerite Perret

Center for Kansas Studies Sponsors Fiber Artist Fiber artist Joleen Goff currently lives in Warrensburg MO, but her most powerful memories are of her childhood in Kansas, and her

|

|||

.

.![[graphic: cut of meat]](images/porkchop.jpg)

![[graphic: lotion bottles]](images/bottles.jpg) abor intensive today, but it was even more so in the period before bar codes. Freight arrived on Wednesday around mid afternoon from a small wholesaler who operated out of the village of Paradise, one of a series of communities along state highway 18, most of which were athletic rivals of the Tipton Cardinals. When the freight arrived at the store, we were expected to be there. In my last pre-school Christmas I remember getting a print set with inkpad and individual letters and numbers. Whether by design or not, the print set introduced me to the task of marking prices on individual cans and packaged goods before they were shelved. The boyhood bliss of summer afternoons spent at Carr Creek, the “railroad bridge” or at the baseball diamond, where balls hit off the north side of public school in right field were in play, always made discharge of this weekly obligation difficult.

abor intensive today, but it was even more so in the period before bar codes. Freight arrived on Wednesday around mid afternoon from a small wholesaler who operated out of the village of Paradise, one of a series of communities along state highway 18, most of which were athletic rivals of the Tipton Cardinals. When the freight arrived at the store, we were expected to be there. In my last pre-school Christmas I remember getting a print set with inkpad and individual letters and numbers. Whether by design or not, the print set introduced me to the task of marking prices on individual cans and packaged goods before they were shelved. The boyhood bliss of summer afternoons spent at Carr Creek, the “railroad bridge” or at the baseball diamond, where balls hit off the north side of public school in right field were in play, always made discharge of this weekly obligation difficult.![[graphic: wrapped hard candy]](images/candy.gif) result, we were showered with Christmas gifts that were more befitting a family with a significantly higher income. Like those of children today, our letters requesting gifts were sent to Santa at the North Pole, but we selected the gifts from a catalog issued by Bennett Brothers, a giant Chicago wholesaler. As youngsters we never made the connection—the magic of Christmas!

result, we were showered with Christmas gifts that were more befitting a family with a significantly higher income. Like those of children today, our letters requesting gifts were sent to Santa at the North Pole, but we selected the gifts from a catalog issued by Bennett Brothers, a giant Chicago wholesaler. As youngsters we never made the connection—the magic of Christmas!![[graphic: running man icon]](images/runningman.gif) contact any of the following people:

contact any of the following people:

![[spoon graphic]](images/spoon.gif)

connection to her grandparent's farm. She notes that "My physical connection to the farm began as a newborn in 1958 and ended in 1996 when my own two sons were two and five years of age and my grandparents moved from the farm into town. Although my physical presence on the farm has ended, my emotional connection to my grandparent's farm has continued to provide spiritual sustenance and helped shape who I am as an artist and person."

connection to her grandparent's farm. She notes that "My physical connection to the farm began as a newborn in 1958 and ended in 1996 when my own two sons were two and five years of age and my grandparents moved from the farm into town. Although my physical presence on the farm has ended, my emotional connection to my grandparent's farm has continued to provide spiritual sustenance and helped shape who I am as an artist and person."