The Kansas author I am featuring for December 2000 is Tetsuro Takahashi

_____

_____

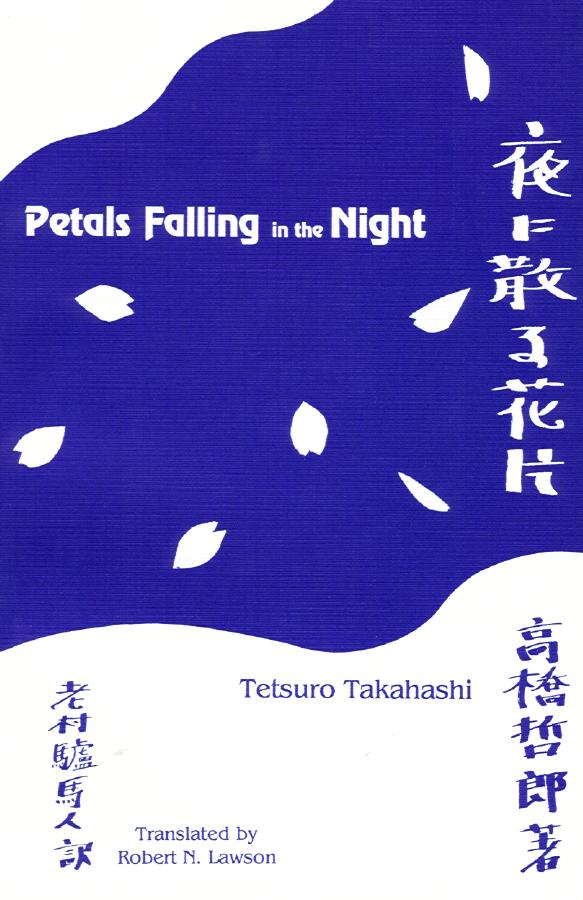

Tetsuro Takahashi Petals Falling in the Night

The Kansas author I am featuring for December 2000 is Tetsuro Takahashi

_____

_____

Tetsuro Takahashi Petals Falling in the Night

Dr. Takahashi is a Japanese psychiatrist, trained at Tokyo University, the same university as all five of the major twentieth-century Japanese novelists I have termed the "big five," and the eight short stories published here in Kansas as Petals Falling in the Night were written, and most were published, in Japan, while he was a practicing psychiatrist there, before he came to Topeka's Menninger Foundation for post-graduate work in psychiatry, then passed the exams to become a certified physician here, then a supervisor at the foundation, then went through the more rigorous program to become a psychoanalyst. More recently, after doing many workshops there over the years, he has returned to Japan, to practice in Osaka, as the only Japanese psychoanalyst who has completed a full training in the United States.

I translated the eight stories in Petals Falling in the Night from the Japanese into English, working first with Dr. Takahashi's wife, Akemi, on the prize-winning story that is the longest, "The Clock," while Dr. Takahashi was still heavily engaged in meeting professional medical requirements here, but, later, I worked with him on the translation of the other seven stories. I have never had the fluency in Japanese to publish a translation without revising carefully with native Japanese assistance, but, in this case, I had the authority of the author, whose English is very good. When it came to publishing the book, though, I think the thing Dr. Takahashi was proudest of was that he and his family had done the illustrations for each of the eight stories, and the cover design, while I know the thing I was proudest of was that he had allowed me to do the calligraphy for the title in Japanese that introduced each story. But both of us are proud of the book, and, with this book, I maintain that Tetsuro Takahashi is a Kansas author, with a book for sale (but getting close to being out of print, so hurry, if you want a copy) which, though published by Repha Buckman's Tri-Crown Press, in Sterling, KS, can be purchased, as most of the other books can, from The Woodley Press, Washburn University, Topeka, KS 66621, for $5.00, plus $1.50 for postage and handling.

I offer as a sample one of the shorter stories, and my favorite, A Happy Home, the translation of which was also published in Short Story International in 1984 (the Japanese original in Katei no Tomo in 1966).

I had made an appointment, and Director Iwahisa appeared immediately. Holding a pipe, black and shiny from habitual use, between his teeth, he said, "I've tried to think of what we chould talk about . . . and, well . . . since it happens my work is with sick people, perhaps stories of sickness are all I know. On the other hand, it is my belief that it is possible to find the way back to health out of sickness."

He drew his eyebrows together slightly and looked up at the ceiling, as he puffed on his pipe two or three times. Then, as if suddenly coming to a decision, he turned and said, "Well, suppose we proceed in that spirit, and you are free to draw the conclusions you choose from the story." And he gave me a sly little smile.

"There is a sixteen-year-old boy named Mitsuo in my hospital. He is a youngest child, separated from an older brother and two older sisters by a number of years, and he was raised by parents who doted on him. Then, when he was in the fifth grade, his parents were killed in an automobile accident. At that time, they say, Mitsuo remained sitting in front of a Buddhist altar for two or three days. After that, for whatever reason, he increasingly avoided other people, and, becoming easily moved to violence, got so bad that, in the spring of his second year of middle school, he was hospitalized.

"Mitsuo's older brother evidentally took it as quite a shock when his brother was diagnosed as insane, which was natural enough in a young man of twenty-five who was assuming the responsibility of three younger brothers and sisters and struggling to carry on the family vegetable business. But, as a result of treatment, Mitsuo's condition gradually improved, and his brother's face began to regain some of its brightness. He thanked me again and again.

"Then came a subtle change in attitude. Mitsuo frequently went home for one night, but when a date for his leaving the hospital completely began to be discussed, his brother's visits became less frequent. Finally, he just quit coming, and failed to respond to my urgent appeals.

"That summer there were the persistent voices of the cicadas in the pine trees surrounding the hospital, that winter there was the melting of the traces of accumulated snow . . . then the time came again when the branches of the hospital's double-blossomed cherry trees began to bend under the weight of their petals. Still the older brother did not come. Mitsuo's condition, which had been improving every day in anticipation of leaving the hospital, suddenly became worse when his brother quit coming. His antagonism toward the nurses, and toward me, especially, was violent, to the point that he would finally just run from us if we called out to him. But even that was not so unreasonable, was it? It was a matter of being identified with his brother in having betrayed his trust."

Saying this, Director Iwahisa rose from his chair and, turning his back to me, looked out of the window. Several patients had gathered under the eaves on that side of the hospital, seeking a warm place, where there was sunshine. After a time, the director continued.

"But then, just as dawn was breaking after a long sultry night in May, as I was rubbing my rather swollen eyes and sticking my arms into my hospital robe--almost a year later--the older brother appeared. His eyes were bloodshot, and his face indicated that he had been badly frightened. I wondered what had happened.

"'Doctor, I know there is no excuse, but, to tell the truth, when the time for my brother to leave the hospital was getting close, I got to worrying whether he might have a relapse, or whether everyone would come to know that it had been mental illness. So, to postpone the time of his coming home, I decided just to shut my eyes and ignore it. That way, for this one year at least, we three brothers and sisters have led peaceful daily lives. But last night I had terrible dreams. Then, feeling compelled to tell you about them before the impression was lost, Doctor, I came running here to you.

"'Last evening was hot and muggy, and the air just seemed to close in on you. When I was going home alone in the dark, from a business association meeting where we may have had an extra cup of sake or two, I looked up in the sky and saw a full, peculiarly orange-colored moon hanging there. I was suddenly taken with a chill which made me tremble. Then, after I had gone to bed, I had this dream.

"'I was walking all by myself, on a path on which, with each step I took, the white dust rose up. The path soon came to a mountain, and wound its way to the edge of a cliff looking down into a deep valley. Suddenly I became aware of someone else moving on the path, some distance in front of me. It was an old man, shuffling along with a little girl on his back. Both of them were dressed in rags. When I saw the child's face, I gasped. She was horribly ugly. One eye was gone and the other, as large as a cow's, was filthy with mucus. One side of her mouth was twisted, a huge eyetooth sticking out from between the torn lips. They soon found their way to the top of the cliff. The old man put the child down and spoke to her, as if he were persuading her of something. The two words "double suicide" flashed across my mind. I tried to shout, "Look out!" I wanted to call out and rush forward, but my mouth remained closed and, for a moment, my legs would not move.

"'Then, just like that, the old man faced the abyss and threw the child into it. It was as if the red floral design on the ragged ends of her coat was burned into my eyes as she fell.

"Stop! What are you doing?" The loudness of my own voice amazed me. I was outraged by the old man's inhuman behavior.

"'Then, unperturbed, he quietly turned to face me. A subtle smile surfaced on a face as lusterless as a withered wood carving. Much to my surprise, he was smiling at me, intimately. And, in response to my shouting, he merely whispered. A voice as hollow as if it were coming from a cave echoed in my own chest.

"'"You, too . . . if you are honest about it," the old man chuckled, from deep in his throat, then flung himself from the top of the cliff as well.

"'I woke up soaked in a cold sweat. But in a little while I evidently fell back asleep. Then I had a second dream.

"'The brightly colored fruit of a persimmon tree hung like bells, in the warm rays of the sun, over the roof of a straw-thatched cottage. The members of the family in this isolated farmhouse were contentedly doing just what they pleased, as it appeared. The men were playing chess, sitting cross-legged in the sun. Several women were weaving straw sandals in the earth-floored section of the cottage. By a large hearth an old woman was holding a cat and tending the fire with fire tongs. The "shun shun" of an iron kettle over the low hearth fire could barely be heard, the light steam wavering up to the ceiling. The scene was a picture of tranquillity.

"'Suddenly the sliding door clattered open and a child came tumbling in, as if pushed in by the sunshine. It had a large wound, and its bloody naked body was smeared with mud, so that a dark stream ran down as the child rolled on the dirt floor and wept and screamed. Its screams and groans were so loud that they shook the little cottage.

"'But there was no reaction. The men, the women, the old woman, all remained in the same postures, as if nothing had happened. Only the warm sunshine, that had burst in with the child, seemed bewildered as it enveloped the screaming form. The strangest thing of all was that these peaceful faces reminded me of the faces of fish.

"'The minute my eyes popped open I thought immediately of Mitsuo, and I came running to you.'

"When he stopped talking the older brother finally seemed to calm down, even breathing a sigh of relief," Dr. Iwahisa remarked.

"Then what happened? What about Mitsuo?" I felt compelled to ask. Dr. Iwahisa, without saying a word, pointed out of the window. There was a young man sitting all by himself, some distance from the patients who were sitting in the sun. He sat hugging both knees, and hardly moving, in a posture suggesting that he was seriously ill.

"After that incident," Dr. Iwahisa continued, "his older brother became actively involved again, for a time, and Mitsuo began once more to be in better spirits. But then there was talk of the brother getting married, and, again, he became remote. I sent for him and questioned him very sharply, but his attitude had changed completely. He coldly remarked that, though he might be Mitsuo's brother, he was not responsible for his birth. He would assume the liability of the hospital expenses, but--he was quite definite on this point--he would not take care of Mitsuo after he left the hospital. As I persisted in trying to persuade him otherwise, he said, 'Why don't you take charge of him yourself, Doctor? Just as with you, the fact that Mitsuo and I encounter one another in this life is nothing but coincidence.' As he responded with that comment, a smile raised the edge of his moouth on one side.

"When I noticed that smile, I felt as if I could also hear the old man's chuckle in the dream he had told me about, with a horrible clarity."

The hospital director fell silent, and quietly closed his eyes.

My heart was heavy on the way back from the hospital. After all, it did seem that a happy home had to turn its back on misfortune for the sake of the family's tranquillity. The sea breeze, that had felt so refreshing earlier, now seemed to penetrate my body with an unpleasant dampness. I turned up the collar of my overcoat and hurried along the dark path, wondering what title to give to today's story.

* * * * *

I am pleased to be presenting Dr. Takahashi as Kansas author for the

month of December, for I am making a major transition to the Japanese elements

in the last half of my novel, and introducing the longer tradition of Japanese

literature, by considering the great medieval classic, The Tale of

Genji.